Working Smart, Not Hard: Lessons From a Decade of Swimming Against the Current

Success doesn't require working harder, it requires working on the right problems. Why choosing the right goal matters more than the amount of effort you pour in.

TL;DR: Hard work on the wrong problem does not fail fast. It fails slowly. It creates just enough progress to delay the moment when you are forced to ask harder questions. After a decade building MadKudu, I learned that execution excellence can hide market problems, and that the real skill is choosing problems where your effort compounds instead of evaporates.

The seductive lie of hard work

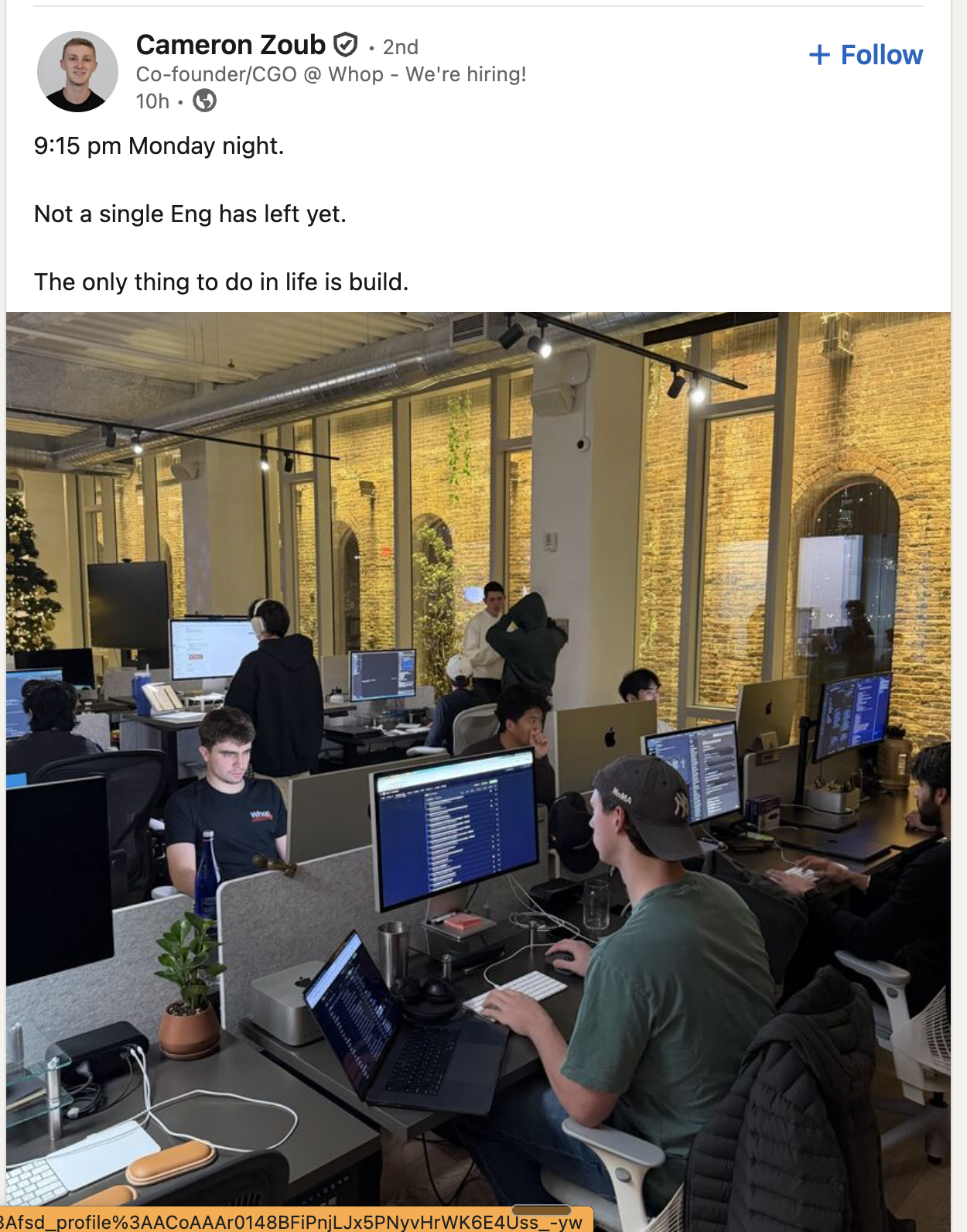

Tech loves a productivity myth. The louder corners of the industry still glamorize 90-hour weeks, 9-9-6 schedules, and the belief that grit alone separates winners from losers. It is a powerful story because it feels controllable. If you simply push harder than everyone else, you deserve to win.

Building something that matters is more important than working harder

I believed that story for a long time.

Hard work is necessary. But when applied to the wrong problem, it does not fail fast. It fails slowly. It creates just enough progress to keep you committed, just enough momentum to make doubt feel premature. For strong teams, this is the most dangerous failure mode of all.

What made it harder to see was that the business never flatlined. Growth came in spikes. Strong quarters followed by plateaus, then acceleration again. Each surge felt like proof that we were close, close to product‑market fit, close to escape velocity, close enough that questioning the fundamentals felt irresponsible.

One signal stands out in hindsight. No matter how much we executed, our website traffic barely moved. Everyone in the industry seemed to know who we were, yet awareness refused to grow. At the time, we told ourselves this was a saturated beachhead and that expansion would come later. Now I see it as an early hint that the ceiling was lower than we wanted to admit.

MadKudu was built by some of the most brilliant, dedicated people I have ever worked with. Absolute beasts. People who could outthink, outbuild, and out‑execute just about anyone. We wore our perseverance like armor. We were the team that never died, the cockroaches who survived every extinction event in our market. One by one, competitors vanished or tried to sell to us. We were still standing.

And yet, we were standing still.

Hard work kept us alive. It also kept us from seeing the problem clearly.

MadKudu: a decade of working incredibly hard on a very hard problem

There was no single moment when it became obvious we were swimming against the current. It was a slow accumulation of evidence that always felt explainable.

Our customers loved us. Our NPS was strong. Our content engine consistently generated interest. Enterprise teams spoke highly of our precision. These were all true signals. But they were also incomplete ones.

Beneath the praise, the business struggled to grow in ways that mattered:

- We couldn't reliably transition from founder‑led sales to a scalable, quota‑carrying motion.

- Web traffic grew, but not fast enough to build real inbound momentum.

- Prospects understood our value, but the complexity of the problem made the story hard to tell simply.

- And perhaps most telling: every competitor was either shutting down or being acquired for disappointing multiples.

Looking back, that last point should have been a giant neon sign. We weren't the exception in a broken market. We were the last survivors of it.

But our team was elite, so we kept the boat moving. When you have world‑class talent, you can fight upstream for a very long time. You can rationalize friction as "normal." You can make unnatural things work. You can convince yourself that if you just execute a bit better, you'll break through.

Execution was not our problem. The problem was the problem.

How execution excellence can hide a market problem

One of the clearest examples of this at MadKudu was our onboarding and customer success motion.

We built an extraordinary team of customer success engineers. They were deeply analytical, technically strong, and unusually good at understanding business context. These were people who could reason through messy data, internal politics, and ambiguous goals, then still help customers get real outcomes. They were the kind of talent that rises quickly at firms like McKinsey or BCG, strong analytical minds with a knack for business.

That team became one of our greatest sources of pride, and one of our biggest blind spots.

Even our smallest customers often required what was effectively PhD‑level problem solving to get value from the product. Customers did not always know exactly what they wanted to do, or how to operationalize the insights we provided. Our team would step in, bridge the gap, navigate internal politics, and make it work. The impact was real. It showed up clearly in G2 reviews and customer testimonials, which consistently praised the onboarding and customer success experience.

From the outside, this looked like progress. We even built product to help this team move faster and scale their efforts. But in hindsight, what we were really doing was compensating for a structural limitation. Customers were not willing to pay for very expensive consultants, yet the problem itself demanded consulting‑level effort. The product accelerated implementation, but it did not eliminate the underlying complexity.

At its core, the challenge we were trying to solve was not purely a data problem. It was a change‑management and internal‑politics problem, informed by data analysis. We focused on building the part that could be productized. The rest was handled heroically by our team. That combination made the business look healthier than it truly was.

We felt like we were making steady progress toward simplification. In reality, we were using exceptional people to make an inherently non‑SaaS problem behave like one.

This was the trap: we were simply too good at keeping the business alive.

A strong team can create the illusion of progress in a stagnant market. You can paper over structural issues with clever GTM patches. You can compensate for a difficult product with heroic onboarding. You can convince yourself that "just a few more quarters of focus" will get you over the hump.

But no amount of operational excellence can turn an uphill climb into a downhill one.

What we mistook for resilience was, in reality, a kind of inertia. Our ability to grind became the very thing that obscured a deeper truth:

Even with perfect execution, this business was unlikely to scale the way we wanted it to.

And that realization did not come in the early years. It came only after raising a great Series A from great VCs, and then failing to show meaningful revenue growth for a full year.

What changed was not our execution. It was demand.

Almost overnight, deals that used to close with familiar buyers at familiar price points became harder to land. Sales cycles stretched. Pipeline thinned. The volume of available opportunities dropped sharply. CFOs were suddenly far more cautious, budgets were scrutinized line by line, and discretionary spend all but vanished. It felt like we had lost our PMF, and we had.

What made this especially disorienting is that nothing about our motion had fundamentally changed. We were talking to the same types of companies. We were selling the same value. But the market no longer pulled. The ambient demand that had made progress feel inevitable in 2021 simply wasn't there anymore.

The macro environment had shifted. The demand surge had evaporated. And once that tailwind disappeared, the underlying fragility of the business was exposed. The valuation we needed to grow into was no longer compatible with the reality of buyer behavior.

This is when the story should have changed. But instead, we encountered the next trap.

Why letting go is so hard, and why acknowledging it felt like relief

Letting go of the original business should have been a gut‑wrenching, identity‑shaking moment. But it wasn't. It was relief.

The emotional difficulty wasn't in admitting we needed to pivot. The difficulty came from everything surrounding that decision:

- Investors who still wanted the original story to work

- Millions of ARR that felt irresponsible to abandon

- Customers whose trust we deeply valued

- A team that had poured years into mastering a brutally hard problem

None of these pressures were malicious. They were simply the natural forces that keep founders anchored to the past. Sunk costs accumulate quietly. Identity solidifies subtly. The business becomes a ship that feels too heavy to turn.

But in our case, once my cofounder and I finally said the truth out loud, the weight lifted instantly.

We were no longer debating tactics. We were finally debating reality.

The opportunity‑cost framework I wish I had used earlier

Here is the lesson I wish someone had forced me to internalize in year two, not year ten.

Every year you commit to a startup is an investment. Not metaphorically. Economically.

If I took a role at another high‑growth company, the combination of compensation and equity would be worth roughly $1M per year. So by choosing to keep building MadKudu, I was effectively investing about $4M of opportunity cost every four‑year cycle.

Founders rarely see it that way. They see staying as the default and leaving as the disruption. But that's incorrect. Staying is the active decision. Staying is the bet.

A better mental model would have been:

Each year, imagine you are a VC deciding whether to invest four million dollars into this business. Would you do it?

- With the information you have now

- With the market signals you're seeing

- With the performance trajectory in front of you

If the answer is yes, great. If not, you must pivot, restart, or exit. Because your time is the most expensive check being written.

We should have revisited this question annually. And every quarter when things were not obviously compounding.

What I see clearly now

With distance, two things are obvious.

One: our team's brilliance and resilience were double‑edged swords. Those superpowers allowed us to survive far longer than the market justified. We could push through friction that should have signaled a change in direction much earlier.

Two: we probably should have begun searching for an exit or a hard pivot sooner. That does not diminish what we built. I will never regret the culture, the friendships, or the craftsmanship. But our determination made the path harder than it needed to be.

In the end, MadKudu found a great home. But the clarity I have now only highlights how much energy we invested in a market that was never going to reward it proportionally.

Actionable guidance for founders and early employees

Here are the signals I wish I had treated with more gravity. One matters more than all the others.

1. If your business only moves when YOU push it manually, it's not a business. It's a project.

This is the signal I would watch above all else.

In every truly iconic company I have seen up close, the hard part was keeping up with demand, not manufacturing it. Teams worked long hours because customers were pulling faster than the organization could respond. In our case, we worked hard to create demand: educating buyers, shaping their thinking, helping them make sense of their own data. That effort created momentum, but it was not latent demand for the product itself.

If you are not constantly feeling demand pressure, you should seriously question whether you are in the right place. At that point, the hardest work should not be execution. It should be finding a market where pull already exists.

2. If every strategic conversation ends with "we just need to execute better," you are probably lying to yourself.

Execution issues rarely persist for years in strong markets. When every new hire struggles despite strong hiring, it is often a sign of market friction, not individual failure.

3. If every competitor is dying or selling for weak multiples, that is not a sign you're the strongest. It's a sign the tide is out.

When an entire category struggles, demand is usually the constraint. Survival alone does not indicate momentum.

4. If your product requires heroic onboarding or PhD‑level talent to implement, your ceiling is lower than you think.

Complexity absorbed by people instead of eliminated by the product is a warning sign. Ease is a feature. Ease is a moat.

5. If your Series A expectations require growth the market cannot support, the valuation becomes a countdown timer.

You cannot outwork macroeconomics or buyer behavior.

6. If acknowledging the truth feels like relief, you've waited too long.

That emotional signal is often the clearest one. Actively listen for it earlier.

Conclusion: Working hard is not the problem. Working on the wrong thing is.

Hard work is essential. But hard work is not the differentiator. The differentiator is choosing a problem where your effort compounds instead of evaporates.

A great market makes average execution look brilliant. A bad market makes brilliant execution look average.

What makes this harder today is that product-market fit is more fluid than it has ever been. Markets shift faster. Buyer behavior changes abruptly. New technology rewires expectations in months, not years. Signals that once took a decade to surface now emerge in quarters.

That means the real risk is no longer failing. The real risk is staying busy in the wrong place.

If you are working incredibly hard but constantly pushing demand uphill, pause. If your team is exhausted not because customers are pulling too fast, but because you are manufacturing momentum quarter after quarter, pause. If your calendar is full and your roadmap is crowded, but the business only moves when you apply force, pause.

Because grit will not save you from a market that is no longer there. And execution will not rescue a problem that should not be solved as a company.

MadKudu taught me this the hard way. For ten years, we swam against the current with a world-class team. The lesson was not about effort. It was about honesty.

In the end, the people always make it worthwhile

Working smart begins long before the work itself. It begins with asking a question most founders avoid for far too long: